If this is your first encounter with the comparison between Flesh and Blood and Fighting Games, we recommend you cycle back to Dylan's first article, Flesh and Blood is a Fighting Game. This is the 4th in a series redefining the way we talk about FAB decks and strategies, following articles on Rushdown fighters and All-Rounders.

If you have ever made the transition from one card game to another- as I have, many times- you come to recognize certain key traits which carry over from game to game. There are core concepts which almost always apply, which makes for a nice transition from a game like Magic to One Piece, for example. If I like "Mono-Green Stompy" decks in Magic, I will probably like "Green Kid" decks in One Piece.

Flesh and Blood, however, does not fit here. At least, not for me.

My anecdotal experience is that I really, truly do not enjoy “control” decks in card games. I like to play defensively, but I do not enjoy when my gameplan exists on the margins of the stack or end step. I do not enjoy winning the game by sticking a powerful threat on the board. Those play patterns are so unattractive to me, I would rather play a different game than play that archetype.

However...

I love playing what are considered “control” decks in Flesh and Blood. My first love was Prism (though, I never got a chance to play the deck); Iyslander is one of the most fun characters in FaB due to her non-linear gameplan; and Dromai is my current “main” deck. I play Dromai more than any other hero. In fact, she is the hero who got me back into the game after a brief step away.

There are a couple caveats to all these, of course. Some players consider Iyslander a midrange deck, for example. Dromai’s current most popular variant is the rushdown deck pioneered by Mara Faris. I also never enjoyed playing Oldhim (a character who, I would argue, does not fit a control label).

I believe that the reason I enjoy “control” decks in FAB - and not in Magic - is simply: in FAB, control is really “Zoner”, and I love to play Zoners like Guile in every Street Fighter.

The Origin of "Zoner"

The term “Zoner” comes from the idea that a fighting game stage is made up of various “zones.”

The above image is the training stage from Street Fighter 5. This is where players will go to measure exactly how long their attacks are, practice combos, and try to find answers to things their opponents are doing. In this image, you can see the play area is broken up into a grid which coheres to the X and Y axis determined by the red stripes. In any given fighting game, each player will start on one side of where the lines intersect.

From that image, you can see that the two omnipresent zones are the ground and air zones. There’s are also short, medium, and long range “zones,” which shift based on the where the players are in the stage.

In Flesh and Blood, most characters really only have one zone to contend with: the Combat Chain. Zoners in FAB get to add an extra layer to that in how they can manipulate and upend the core concepts of the Combat Chain with their permanents and afflictions. Dromai, after having played a dragon, now represents an infinite damage source until it is killed or destroyed with a Phantasm popper. This completely upends the calculus, as all other heroes’ repeatable damage sources come from their weapons, of which they can have a maximum of two, whereas Dromai and Prism can have… as many permanents as they can fit in their deck!

But, returning to range zones, here are some examples.

A Rushdown character most often excels in the short ranges, and oftentimes in the air zones.

An All-Rounder will excel in the medium ranges and sometimes the air zones.

A Zoner, by contrast, only truly excels in the long-ranges, and so uses their abilities in the long-range to deny their opponent access to the medium, short, and air zones.

A Zoner is a wonderful proposition to the players who despise getting hit, or playing risky. Unique from our previous two fighting game archetypes (Rushdown and All-Rounder), it has a completely different gameplan. The gameplan of a Zoner in a fighting game is to maintain an effective distance, so as to chip the opponent’s life total down from relative safety. Zoners excel at maintaining a safe distance from their opponents, often utilizing long-range, sometimes even full screen attacks which cause major difficulty for their opponent to get close enough to start a combo string.

Defensive Denial with Guile

To further illustrate this, let’s take a look at one of the most famous zoners in all of fighting games: Guile from Street Fighter. Guile is a very simple character to understand on first glance, though his gameplan can become quite complex depending on the matchup and player skill.

First, Guile’s main tool for victory is his 'fireball' (or 'projectile attack') called “Sonic Boom” - one of the most powerful Fireballs in all of Fighting Games.

And close behind that, his 'dragon punch' (or 'anti-air attack') called “Somersault Kick” - one of the most iconic special attacks in all of Fighting Games.

This second attack is so famous, it has birthed its own name. While rising uppercut anti-airs come from the Shoto characters Ryu and Ken, Guile’s is called a “Flash Kick,” because of its incredibly fast startup animation and absolutely massive hitbox. This term is still used today by more Charge-based fighting game characters. (More on that in a moment.)

These two moves make up a defensive strategy which is extremely difficult to counteract. A well-trained Guile can spend the entire match simply throwing Sonic Booms and waiting for the opponent to start jumping over them, so as to punish them with his Flash Kicks.

The way his kit is built into his gameplan gives us another clue. Where Ryu and Ken have to input the directionals forward, down, forward, and then punch in order to execute a dragon punch, Guile simply has to hold “down” to “charge” his Flash Kick. Guile, then, is also considered a “Charge” character, because his specials all come from “charging” specials, which simply means “hold a directional input for long enough, then input the opposite direction and a corresponding attack button.”

It is extremely important to note the difference here, because of how this bears out in gameplay. One would think, when looking at the two moves (dragon punch and flash kick), that they are effectively the same move. They both deny the air zone to their opponent and deal a good amount of damage. The distinguishing factor is risk, though. Ryu and Ken, as previously stated, must input “forward, down, forward.” By inputting forward, they lose their ability to block.

In contrast, Guile can hold “down” and “back” to charge his Flash Kick, so Guile never has to release his block to charge his moves until it becomes relevant to do so. This immediately places Guile in a much more defensive posture. In order to do his offensive moves, he has to block.

This also informs us of his gameplan - that being he is almost always on defense, and simply reacting to his opponent’s advances. This slight variation has massive implications for the two archetypes, and thus is crucial to understand before we move to the next Zoner. I bring this up specifically because, as previously stated, all characters in all fighting games are trying to kill their opponent. There is no “alternate wincon,” like "gaining the city's blessing" or "milling the opponent". The goal for Guile is the goal for any character: reduce health to zero.

The minutiae of that, though, is where the main differences lie. Guile is extremely frustrating to fight against, and in that frustration lies his greatest strength: when you are playing at Guile’s tempo, you will make mistakes. These mistakes are what Guile will take advantage of to win the game.

Keeping Your Distance

Now let’s look at a more obviously Zoner: Dhalsim.

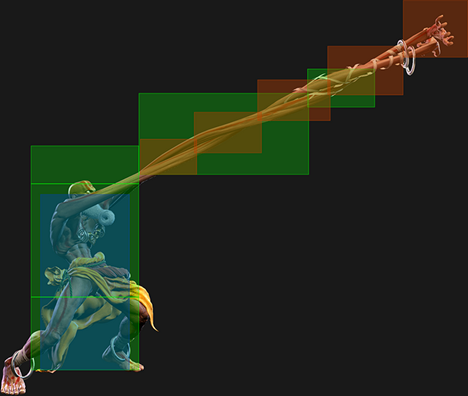

This image shows a pretty wonderful example of “long range attack.” Dhalsim is the quintessential Zoner. Where Guile can pivot into some nasty offense, Dhalsim uses a bag of tricks alongside his ridiculously long range to truly chip their opponent down to zero.

What’s critical to understand about this particular attack is that it is considered a “low,” attack, meaning it can only be blocked by holding “down,” and “back.” This is important because holding “down,” requires you to stop moving just slightly more than simply having to hold back. Dhalsim can spam this attack against a lesser skilled player to lay on piles of chip damage over the course of the round.

This totally insane move is called “Yoga Lance.” It is an Anti-Air move which reaches so far, there’s almost no chance for a full range opponent to gain any ground via jumping.

I included the hitboxes and hurtboxes in this image as well, to illustrate another point. The red squares indicate the “hitbox”: that being, the area which, if the opponent’s body intersects, it will cause damage. The green squares are called a “hurtbox,” which means, if an opponent’s “hitbox” intersects, it will cause damage to Dhalsim. What’s important about this specifically, is that the “hitbox” of this move is disjointed. There are two and a half squares with no hurtbox! That means, if the Dhalsim player is aware of this, they can abuse this to no end, as trying to punch Dhalsim’s hands will yield no benefit for the opponent.

This is crucial in my analysis of Zoners in FAB, as I view Dragons, Frost Hexes, Auras, etc., to be things in the game which have no “hurtbox.” They are free damage, free tempo, free ways to push the dial in your favor.

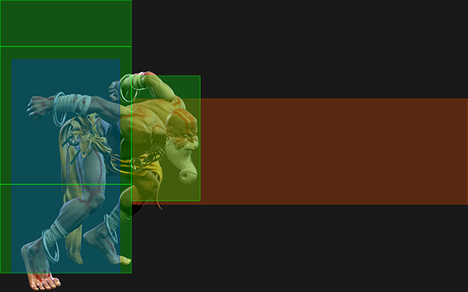

Here’s another example of a move with no hurtbox: Dhalsim’s “Yoga Flame.”

With this move, Dhalsim blows fire from his mouth, and the red “hitbox,” indicates the damaging area. If the opponent is out of range to punch or kick Dhalsim, they simply must block or take the hit.

What’s more, if Dhalsim ever finds himself in a tight spot, he can input the move “Yoga Teleport.”

This move allows Dhalsim to teleport to various locations around the screen, thereby resetting neutral if he needs to, or even getting a tricky teleport into a more advantageous offensive position when their opponent is paralyzed by the constant, long-range onslaught Dhalsim can put out.

Zoners in FAB

With all that explained, what is the takeaway from Zoners in Fighting Games as they relate to Flesh and Blood?

I contest, as earlier stated, that while many concepts translate from game to game, especially card game to card game, what Magic considers tempo and what Fighting Games consider tempo are very different concepts. Zoners in Fighting Games use their long-range and particularly strong defensive attacks to control Tempo.

Tempo, in games, refers to the pace or rhythm at which the game is being played. It involves gaining and managing advantage: which is, put simply, “progression of the game in your favor.” Tempo ebbs and flows between players based on their respective advantages, cards played, etc.

Tempo in FAB famously comes from cards like Command and Conquer, which destroys an arsenal card, or Channel Lake Frigid, which denies your opponent from playing their cards effectively. Tempo also comes from landing a card like Snatch, which allows the player to draw a card, either for arsenal, or for one more attack.

The idea of Tempo is born out in cards used to block and cards used to attack. If I force my opponent to block with two cards for my one, I have won the exchange. If I land a Sonic Boom (the Guile version, not the Wizard version) against my opponent, I get value chip damage, stall them for time, and force them to come to me how I want them to.

Zoners, in FAB, have a unique way they interact with Tempo, and to talk about that, I will list who I believe are the current zoners in Flesh and Blood: Dromai (the big dragon variant), Iyslander, Prism, (Item) Dash, and (Ice) Lexi.

The most famous of the Zoners, in my opinion, are the Illusionists: Prism and Dromai. This is because they interact with the shifting tempo the most on a turn-by-turn basis. Illusionists must often make very strange plays in the context of a Flesh and Blood match, taking significant damage or pitching very strangely in order to set up board presence. Everyone has experienced the “Prism board,” where Prism has a table full of Spectra auras, each of which will require a full turn to remove; or stared down a table of dragons, watching Dromai block with 3 cards every turn, only to play out a Red 0-cost card to give them all go again.

This is important because every card an Illusionist has in play is effectively free damage, because the permanents on board are so difficult to interact with when you only have four cards each turn. A Dromai with a playmat full of dragons has so much attack value in play, she is effectively controlling the liminal space between the players. If she can stave off the attacks from her opponent long enough, all the while chipping damage with her dragons, her opponent will have to pivot off attacking her in favor of killing dragons - and at that moment, Dromai has won the game.

This is also the case for Lexi and Dash. I still have horrifying flashbacks to a dominated Chilling Icevein, or 3 Induction Chambers on board. Once the Zoner gets established in their comfortable tempo, they are humming, and there’s not much anyone can do to steal it back.

Jamie Faulkner, considered by many to be one of the best Dromai players right now, has stated on numerous podcasts that Dromai is “a tempo deck,” first and foremost. The deck is not trying to deal the most amount of damage in the least amount of turns, nor is it trying to land one huge attack every other turn like a Grappler. The tempo/Zoner deck will sometimes block like an All-Rounder, but sometimes won’t block at all. The only thing that matters to a tempo deck is tempo. If I have 3 0 cost Dragons, and a fourth 1-cost dragon in my arsenal, it will take a significant on-hit or an absurd amount of damage for me to consider blocking with my hand, and that is because my hand, effectively, represents 12 life, depending on my opponent’s hero. When each dragon costs a card to remove, either by Phantasm popping or by attacking the dragon directly, I can consider that dragon having given me 3 life or 3 points of value in addition to its attack value.

I say all this not to sway you to play Illusionists; just that this calculus, to me, fits perfectly with the idea of the Zoner archetype in fighting games. Yes, those Ashwings only do one damage each, just like Dhalsim won’t be doing massive combos off of stray hits. Yes, I cannot play a Channel Mount Heroic and beat my opponent to death with absurdly overrate cards. But I have copies of Burn Them All, or Shimmers of Silver with a Genesis in hand. The Zoner, in the context of Flesh and Blood, is constantly looking to create a gamestate which becomes too difficult to overcome, and so the opponent must willingly give up tempo in order to combat it.

Iyslander can be considered an All-Rounder or a Zoner, depending on the deck. Her taxing effects, in my mind, work similarly to Dromai’s Dragons or Prism’s Auras/Angels. By hindering the opponent, they gain life.

If Viserai gets hit with one frostbite, for example, it can change his damage output significantly. Think of a typical Viserai turn cycle of red Mauvrion Skies, red Shrill of Skullform, and a blue pitch. In a normal turn, Viserai can output upwards of 15 damage value from this exchange alone (7 from Shrill, 4 from Rosetta, 4 from Runechants). If Iyslander plays one ice card on his turn, his output changes to 7 because he no longer can attack with Rosetta Thorn, as he only has one resource left in pitch. This doesn’t come from Iyslander blocking Viserai, and that is key; this comes from Iyslander actively not blocking so as to use her cards on his turn to stop him.

The Zoners of Fighting Games are not famous for blocking, so much as they are famous for being difficult to deal with. They work on non-traditional axes to gain significant tempo swings in their favor. In Street Fighter or Guilty Gear, or any Fighting Game for that matter, the non-Zoner must throw out all traditional gameplans in favor of dealing with the full-screen attacks. If the Zoner is good, the non-Zoner will simply never have a good chance to get in on them to do damage.

Now of course, this exchange does not always work. Dromai’s dragons can become a liability to her if their phantasm clause triggers at the wrong time. Iyslander’s frostbite can be rendered inert by a timely Fyendal’s Spring Tunic activation, or simply another pitch card in hand. Dash, too, can simply take too long to set up her game-winning board state, and items do not have any block value.

The risk is high for those heroes who try to gain reward for not threatening their opponent’s hand every turn. So too is this the case for the Zoner in a fighting game. Zoners do not have the ability to flip a switch and become offensive juggernauts. If they land a big hit, their combo options are limited significantly by their offensive kits. Most often, the Zoner's attacks in a fighting game are slow, easy to read, and they cannot compete in the close ranges with a Rushdown or Grappler archetype. If the Zoner gets cornered with no obvious way out, it can effectively end the game on the spot.

The goal for fighting game players, when playing against Zoners, is to identify their tendencies in-game. Perhaps they favor a particular anti-air attack which can be exploited by jumping in a specific way. Or perhaps the Zoner struggles to deal with a particular kind of mix-up. This sort of exploitation of weakness is normal and universal among all archetypes in Fighting Games, but the difference here is, that, Zoners falter and crumble more easily if they can’t execute their gameplan.

Live and Die by Tempo

To conclude our discussion on Zoners in FAB, I want to reiterate that how Zoners examine Tempo is the key. If the opponent comes out swinging like a wild child, the Zoner will have to meet them at their speed to slow them down and put them in their place, where the Zoner will always win. There is no slower match to watch in Fighting Games than the Zoner mirror; similarly, Dromai or Iyslander mirror-matches are some of the weirder matches to watch in all of Flesh and Blood - and it stems from those players understanding the value of each other’s tempo plays so intimately.