If this is your first encounter with the comparison between Flesh and Blood and Fighting Games, we recommend you cycle back to Dylan's first article, Flesh and Blood is a Fighting Game. This is the 3rd in a series redefining the way we talk about FAB decks and strategies, following an article on Rushdown fighters.

As talked about in my video on the Gorganian Tome YouTube channel - as well as the previous article in this series - the long-standing archetypes of Fighting Game Characters is such:

All-Rounder

Rushdown

Grappler

Zoner

Carrying on from our previous article focusing on the Rushdown archetype, I felt it appropriate to move into the category which sees both the second most representation in fighting games and is, in some ways, the core archetype from which all other characters are born. That archetype is the All-Rounder, otherwise known as “Balanced,” or “Bait and Punish.”

Before I do that, though, I want to discuss Midrange and how it functions in the archetype triangle so as to dispel some confusion about what exactly Midrange means.

Midrange is Mid

Midrange is a nebulous concept with many definitions. Some describe Midrange as being a deck or archetype that wins “in the middle of the game” - that being, they are strongest when the game is entering the middle turns, and by that, in Flesh and Blood, I suppose we mean “when both players are at about half their starting life total, and about half their deck has been used.”

In Flesh and Blood specifically, the community has anointed heroes such as Rhinar and Iyslander as Midrange. Though they are vastly different characters in their ideology, game plan, and damage dealing techniques, one can see why they are lumped into the same category.

Midrange, as the term is used in FAB right now, is the idea that you block with some amount of cards from your hand every turn. You never have a defensive turn in which you do not block. This runs counter to the Rushdown gameplan of taking all damage to keep your hand full of cards for longer.

However, Midrange has many definitions. Two stand-out definitions of Midrange in my mind are used in Magic and Fighting Games, which could not be more different from each other. In Magic, an Aggro deck wants to win by turn 4. A control deck would prefer to win the game by turn 8 (or at least have the inevitability locked up), and a midrange deck would like to win the game by turn 6, right in between Aggro and Control.

This timing is key to understanding midrange as a concept in the triangle of card games. They want to stave off aggro long enough to land more powerful creatures. Against Control, Midrange wants to lock up the game before Control can establish their inevitable win condition. The reason this is nebulous becomes obvious upon inspection.

For Magic, a control deck cannot win before a certain Mana threshold. An Aggro deck cannot win if they have played all their creatures out and got them swept by a Wrath of God effect. There are certain conditions in Magic which determine a loss on the spot. If an Aggro deck can kill a Blue-White Control deck before the board sweep, the Control deck never had a chance to win the game.

Determining archetypes based on the number of turns a deck would like to win by in Magic is as easy as it is elegant. In FAB, though, there is simply too much player agency in when someone loses the game. In FAB, a Rushdown deck can block with all 4 cards from hand and be pretty difficult to kill as a result. Bravo, who I categorize as an aggressive Grappler, can draw 3 Crippling Crush hands in a row, locking the game up, despite being a more midrange-y control deck. Iyslander can come out of the gate with some excellent damage spells and disruption effects and effectively win the game as soon as her Rushdown counterparts.

This flexibility and malleability tied to player agency makes it impossible to use Magic archetypes for Flesh and Blood. They do not carry over, and they do not fit with the core game flow set by the team at LSS.

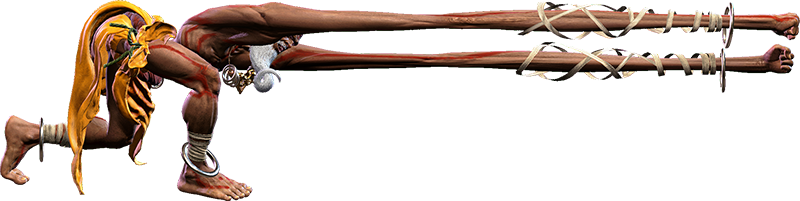

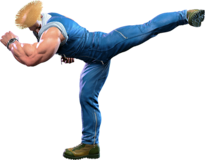

The second definition of midrange, then, can be found in Fighting Games. In fighting games, though, Midrange has a completely different definition. Midrange has been more recently adopted in the FGC (Fighting Game Community) to mean “characters who are strong in the mid ranges.” A middle ranged attack is one that is neither long, nor short. Jabs, like the one seen below, are considered a “short range” attack.

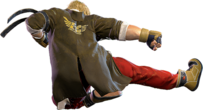

Whereas, the picture below is considered a “long range” attack:

It’s obvious to tell the difference between these two, no? So then, Midrange is exactly what you think it looks like: it is an attack which is effective somewhere in between these two attack types, such as the one pictured below:

And this is ultimately why I wanted to discuss Midrange before discussing all-rounders. It is easy to be confused when comparing Flesh and Blood with Fighting Games and use their terminology interchangeably. A character in a fighting game can be a “Midrange Rushdown” character, because their effective attack ranges are in the middle, and their goal for winning the match is to rush their opponent’s health total down. And so, with that out of the way, we can now examine the All-Rounder archetype.

A Tale of Two Shotos

All-rounders, just like every other archetype in Fighting Games, are categorized by their respective kits or tools. But every character in a fighting game has one win-condition: reduce the opponent’s life total to 0. Because of this, all other interactions a player has with the game must, in some capacity, advance this win condition forward.

With this boundary already determined, the design of characters comes down to each character's respective set of tools and how they are meant to use them. Put simply, the All-Rounder's goal is to play reactively to their opponents, identifying which tools in their kit they should use most often. All-Rounders spend more time blocking than their Rushdown counterparts, waiting for openings to return fire. But this is not always the case; sometimes, the All-Rounder gets off to a great start, and can pummel their opponent relentlessly until they die.

In Rushdown's case, their tools are more catered to attacking quickly, advancing quickly, dealing high damage, and having very few ways of escaping their opponents' damage. If we were to think of a Rushdown character’s kit in percentages, we could say that a Rushdown has a 90%/10% split of offensive moves vs. defensive moves. They also tend to move faster on the screen than their all-rounder counterparts.

All-Rounders are usually 50/50 splits, more or less. Some All-Rounders, like Ken from Street Fighter, are more in the 65/35 range, whereas Ryu has historically been a flat 50/50. You will notice when playing Ken and Ryu, that their moves are very similar.

They both have Hadokens (aka Fireballs).

They both have Shoryuklens (aka Dragon Punches, aka Uppercuts).

And they both have Tatsumakis (aka Tatus, aka Spin Kicks, aka "legs").

These three special moves make up the core of what is called a “Shoto” character. Shotos are a spectrum of All-Rounder, offering offensive- and defensive-oriented variants. These Shotos play very similarly in one sense, but are also extremely different in practice.

For example: Ryu’s Fireball is much faster than Ken’s. Ken’s Tatsu is much faster than Ryu’s. And while Ken’s and Ryu’s uppercuts are largely the same damage-wise, Ken’s reaches very far and is used often as an offensive maneuver, while Ryu’s is more often used defensively.

I should note here, too, that while many shotos have a fireball, not every All-Rounder does. This is important because the projectile ability is a major signifier that a character is actually a Zoner (still to come!), but the Shoto fireballs are a poor zoning tool. They are instead a method by which the All-Rounder character can force their opponent into the ranges the All-Rounder wants them to be in, which is, often “the midrange.”

The Nitty Gritty

The previous section shows the range within the All-Rounder archetype, in that even two characters with many of the same moves can be very different from one another; but it does not explain why this is a “balanced” or “all-rounder” archetype itself.

The reason for that, though, is simple. While the uppercut from before is a move which deals damage, and thereby must be considered an offensive attack, the uppercut is more often used defensively than offensively.

Take this scenario:

Ken has scored a knockdown on his Ryu opponent. While Ryu is laying on the ground, Ken decides to attempt a high-damage combo starting with a jumping heavy-kick.

Ryu, having predicted Ken would attempt to do this, decides to punish the Ken for being so obvious in his gameplan, and does what is called a “wakeup DP”. Wakeup, in fighting games, in when a character does something “on wakeup” or, “the moment the character can be controlled again after getting knocked down.” The DP, or uppercut, hits Ken right out of the sky and sends him crashing to the ground.

This is an offensive maneuver being used defensively, and it happens extremely often in fighting games. This is also why the uppercut move is used more often as a defensive move than an offensive one. Throwing out uppercuts in the middle of a fight is almost certain to spell disaster for the player, because the uppercut move is very punishable when whiffed or blocked.

Now, you may be asking, “Punishable? Whiffed? What are you talking about?” And rest assured, I have been saving that for the respective Flesh and Blood characters, because this is where I think the linkage is clear!

The All-Rounders of Flesh and Blood

For this article, I will be focusing on Dorinthea and Boltyn as my respective All-Rounders: Dorinthea because I find her to be the quintessential All-Rounder character, and Boltyn because he’s a bit like Ken; also an All-Rounder, but more bent in one direction.

When considering the All-Rounder archetype in FAB terms, it can be instantly apparent and confusing at the same time. What isn't an All-Rounder, like Fai, is evident; historically, Fai runs mostly 2-block attack action cards, which makes him weak to tall-damage effects and disruptive on-hit effects. Fai mostly plays with red-line cards, which doubles up the same disruption problem.

Dorinthea, by comparison, runs a rainbow playset of reds, yellows, and blues. She also, very often, runs an entire suite of 3-block cards in her deck.

Dorinthea is very malleable and modular depending on the meta and matchup. If Dorinthea is playing against Bravo, for example, she can sideboard in a slew of Steelblade Shunts to make the Guardian’s on-hit life miserable. Against Rushdowns like Fai and Viserai, she can force them into a constant state of guessing whether or not she has the attack reaction card in hand. Dorinthea, when left unchecked, can race just about anyone she wants to, so long as she can land that first +1 counter on Dawnblade.

Not only that, but Dorinthea, when pushed into a corner, can operate very well off two- or even one-card hands, so long as she can activate her trusty Dawnblade; and if her Dawnblade has a counter or two on it, blocking for 9 damage each turn, while returning 5 or 6 from a pumped up Dawnblade, is a horrifying proposition.

Viserai, by contrast, operates on 3-card or 5-card hands. 1-card hands don’t function, and four-card hands often leave something unusable. Viserai will do everything in his power to maintain the 5-card, and will drop to the 3-card only if he must. It simply takes much more resources and energy for Viserai to conjure his split damage attacks than it does for Dorinthea to swing and stab with her sword.

Briar, another Rushdown, is typically very easy to disrupt so long as her opponent is relatively adept at shutting down the non-attack into attack gameplan; but Dorinthea plays very well around disruptive effects with her reaction abilities.

Even more, while Grapplers and Rushdown can struggle mightily against Zoners like Dromai (because the Zoner is good at maintaining a distance from the two forms of close-range characters), Dorinthea pretty reasonably gains value and advantage from killing dragons, and has just enough offensive go again to deal with Prism's shenanigans.

You can name a trick, and Dorinthea has it. Instant speed plays, damage on the opponent’s turn, pumps, dominate effects, card draw effects. She has it all!

But, she does not excel at any one thing. She is nowhere near as good a defensive character as Bravo or Dromai or Oldhim. Losing pressure with Dorinthea means losing counters on Dawnblade, which can spell disaster for the prodigal swordswoman. So once she is swinging with her sword, she can be priced into swinging it each turn so as not to lose the incredible advantage of Dawnblade counters.

And while her damage is atypical, most often coming from evasive reaction-based damage, it is predictable. Very unlikely will she throw in a surprise attack action card to bolster damage. She doesn’t have any Art of War effects either. What she does have is a weapon that gains power in multiples of three; and so if her opponents know her gameplan well enough, she can be dealt with handily by clever blocking, or one big defensive reaction blowout turn.

But then, just as there’s Ken to Ryu, there’s Boltyn to Dorinthea.

Boltyn, who has received some much-deserved support in Dusk Till Dawn, is also a character I consider to be an All-Rounder. Boltyn plays a similar - albeit very functionally different - gameplan in practice. For one, Boltyn actually plays with attack action cards. Many of his attacks allow him to put a card into his “soul,” which can be cashed in later in the game for powerful effects, such as attacking with his 0-cost weapon a second time, or giving his attacks go again, or - even more extreme - using the cards in his soul to enable a true combo-kill, one of very few in Flesh and Blood.

Boltyn has access to all the same cards as Dorinthea. The core, fundamental gameplan of both heroes is to manipulate the +1s of attacks. Boltyn does so through reaction cards and charging, Dorinthea through her non-attack buff effects like Sharpen Steel and reactions like Out for Blood.

Boltyn can also be supremely tanky and extremely difficult to kill as a result. Almost all of his cards block for 3, and he has the ability to continue to push damage after committing multiple cards to block - albeit, he has a slightly harder time of it. Boltyn’s on-hits can present nasty headaches for the opponent, just like Dorinthea's. I'm thinking of cards like Bolt of Courage, for example, which offers him the chance to draw a card with go again, something not often seen on an attack action card for any hero.

Not only that, but Boltyn creates nightmarish blocking scenarios where spare attacks, cards players are most willing to block with, are penalized because Boltyn’s attacks can gain +1 attack if he has charged his soul.

And while I wouldn’t say the Dorinthea and Boltyn fit perfectly to the Ryu and Ken because neither are necessarily more offensive oriented than the other, they do offer vastly different play experiences despite being, effectively, very similar in terms of play patterns.

The All-Rounder Advantage

To recap my points about All-Rounders and fighting games, I want to start by saying the most crucial aspect of an All-Rounder is their mixture of offense and defense. That All-Rounders are not specialists necessitates that they make up for their problems elsewhere, and that elsewhere in the case of FAB is the ability to modularly function based on what the opponent is doing. Having a more reactive hero can be a huge boon, if the reactive player is very familiar with the gameplans of all the proactive players.

Daigo Umehara - one of the most storied, famous, and successful fighting game players in the world - has played either Ryu or Guile in nearly every Street Fighter game. Daigo is so experienced with these two characters, I genuinely believe he could beat me with his eyes closed. Whenever there’s a major tournament, Daigo is there, having mastered just about everything someone can master in fighting games, and uses these extreme levels of knowledge to pull one over on his opponents with his reactive characters. He always knows what to do, in every situation, against every character.

Now that I am so heavily invested in Flesh and Blood, I often find myself looking to Joshua Lau or Ethan Van Sant for that same experience. Players who know their role in the game so well, who know their heroes and matchups so well, they can adjust and play their cards in ways most players would never even think of, because they are well-rounded and experienced.

The second most important aspect of the All-Rounder is that it is not “midrange.” Midrange is a term which, in my opinion, ought to be retired in FAB, because there is simply too much player agency on when they die. If we want to use the fighting game definition of midrange - that being attacks that reach farther than short-range attacks - that is something I can get behind (Dawnblade + Overpower?), but “win the game by turn 6, after the aggro and before the control,” is not going to cut it. There is too much nuance in a Flesh and Blood match.

And finally, the last thing I want to touch on is Proactive vs Reactive play, and the ability to pivot based on game state, opponent, and even hand structure. Most Rushdown characters cannot pivot away from attacking if they need to. Or rather, they can, but they will do it poorly. An All-Rounder, however, can freely swap between them, playing the long game one hand, then switching to full-on aggression in the next.

Who do you think fits this archetype in Flesh and Blood? In my original video, I suggested Dorinthea, Boltyn, Uzuri, and Rhinar. I should caveat that by saying we cannot forget that Flesh and Blood is a card game, and when you can fill your deck with mostly whatever cards you want, it is hard to say Dorinthea can only be an All-Rounder, or, for a better example, that Rhinar can only be an All-Rounder, because I find that Rhinar can be as much an offensive oriented Grappler as he can be a “block two attack two” All-Rounder.