From my first forays into adulthood, I knew I wanted to be a linguist. When I was in high school, someone who would become a dear friend and colleague (who I asked to proofread this before submitting it) asked me what I wanted to study in college. Truthfully, I had no idea; nothing sounded remotely interesting enough for me to do the rest of my life. He then asked me if I had ever heard of linguistics – his undergraduate and ongoing doctoral degree. From that moment I was hooked, and it’s been one of perhaps a few too many life goals to make a living from it.

In an ever-growing world of interconnectedness, language shift (also called language replacement) is increasingly common. This is the process by which a community of speakers change which language they speak. This occurs for a variety of reasons, such as moving to the language of major economic powers (English, Mandarin, etc.), which can confer the social prestige associated with economic advancement; or as was often the case in the colonial periods, by force – evidenced by the numerous extinct and moribund language families in the Americas and anywhere else powerful countries have extended their reach.

Unfortunately, the list of endangered languages only grows. Conservative estimates predict half of the 7,100 verbal languages – a term I’m creating here to differentiate from sign languages – to be dead, dying, or at least achieving severely endangered status by the year 2100. Less conservative predictions put that figure as high as 90%.

In recent years, there’s been an effort across many communities with threatened languages to revitalize and preserve their community languages. We call this language revitalization. These communities try to support their languages in their current society, usually through a combination of lobbying their governments, community outreach and education, or overall just using the language in place of a wider, more commonly used counterpart. In essence, this is a community taking back linguistic power in order to preserve their culture.

Many of these languages declined due to policies implemented by governments enforcing or discouraging the use of local or minority languages. This can be from a lack of support, such as no government services available in that language (purposeful or not), or assimilatory policies designed to remove the language from being spoken publicly at all, usually with the goal of eliminating the cultural group entirely by assimilating them into the majority.

There have been many failed attempts – after all, it’s no small task – but also a few ongoing success stories. The most famous example is Welsh, but there are efforts all around the globe. Basque revitalization efforts have increased the number of speakers, but that success isn’t accompanied by increased use in day-to-day life. Interestingly, Basque culture is seeing a revival in the western United States as well from historic diasporas. Irish is one of the most famous examples, and has comparatively little official support from the government. It’s largely a speaker-driven endeavor, but is seeing success and even becoming more prestigious in some places.

Another famous example crossed into the world of Rathe with Super Slam.

Māori – or te reo Māori, literally “the Māori language” – is the language of the Māori people in New Zealand, where LSS makes its headquarters. Like many Polynesian languages, Māori began to decline during European colonization. After a nearly century-long period of decline in the face of colonialism, efforts to support and revitalize Māori gained traction in the 1970s, leading to what is now often referred to as the Māori renaissance. This still-ongoing cultural and linguistic revival has made a serious impact on New Zealand. For example, the Māori name for the country, Aotearoa, is widely acknowledged today.

I am not going to make this a colonial period history lesson. First, I am not an expert on Māori, the people or the language. I’m a linguist and an archaeologist; while I am more than qualified to discuss the linguistic devices of Māori and how policy impacts a language – and the tangible impacts those policies have – adequately explaining that history is not something I am particularly suited for. I’m here to explain why Māori Pleiades is important, and a huge win for indigenous linguistics and language revitalization everywhere. An incorrect or poor summation of that history is counterproductive and damaging to that goal.

Second, while The Rathe Times is not afraid to cover important social issues as they pertain to Flesh and Blood, there are sources that are far more thorough and informative than I could realistically be here. If you’re interested in learning about the events that contributed to Māori’s decline, there’s an excellent series of documentaries on the New Zealand Wars by New Zealand public broadcaster RNZ available for free. Additionally, the Wikipedia articles I’ve cited have their sources listed, and those are often available for free as well. It would be wise to look beyond Wikipedia’s summations to get a better understanding of these topics.

Why Revitalization is Important

While on the surface, language revitalization might just look like keeping the language spoken, it goes beyond that. In truth, keeping a language alive is a symptom of broader success. The actual goal is cultural preservation, because when a language dies, the culture often dies with it, and what survives bears the scars of that trauma forever. Even if the culture doesn’t die immediately, it’s usually the mortal blow that will eventually kill it.

A language is more than a communication system; it’s the manifestation of a specific people and place, and the history those share. The knowledge, worldview, and cultural memory of any people are all tied into their language. When a language dies, all of that is lost, and there’s no way to recover it. While a written record does preserve some knowledge, it is not a full replacement. The Ancient Egyptians didn’t record every facet of the world around them or who lived it in. Neither did the Classical Maya, and most Mayan languages are still alive today. Much of the knowledge of their worldview disappeared with Spanish colonization and forced conversion to Christianity. In truth, no society has ever recorded every facet of their culture, even in the age of the internet.

When a language dies, the culture often dies with it.

Even if a given culture managed this impossible feat, written records can become difficult to engage with in a short period of time. For example, Ottoman literature often assumed the reader had competency in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, and it was common to craft wordplay and meaning from this triple competence. Now, only 100 years after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and establishment of modern Türkiye, it can be difficult for today’s Turkish speakers to engage with the Turkish represented in the writings of their great-grandparents’ generation. That’s a short period of time for such a dramatic change! All of this goes to show that written records are not replacements for the living, breathing cultural memory that is a language.

Scientific and historic knowledge is also lost when a language dies. In the case of Māori, much of what we know about moa, an extinct family of large flightless birds, would be lost because the only first-hand human accounts before they were hunted to extinction in pre-colonial times come from Māori oral tradition. Knowledge of medicine, the landscape, and environment are just a few of the practical and scientific fields of knowledge that suffer. For many archaeologists who study the impact of natural disasters on human society, the most practical knowledge they are looking for is how a given culture built their society to handle them, and whether that can be adapted to the infrastructure in societies at the same location now to save lives. Oral traditions of history also perish with language death, along with the perspectives of that culture.

Unless we invent time travel, there is no way to save this knowledge once it is lost. For some languages trying to be revitalized, especially in the Americas, there are large gaps in the lexicon because the language was almost moribund. In many cases, the language’s only fluent speakers are elderly, and few and far between. There’s only so much we can preserve when a handful of people are all that’s left. I’ve personally handled linguistic data from living tribes today, and sometimes what’s been recorded is a pitiful remaining record of a deep, rich tradition. In some cases, those records are all that remains, and it’s nearly impossible to reconstruct the language from them.

The goal of language revitalization is to keep a language from reaching this point, where almost all cultural memory is extinct and knowledge lost.

It’s important to note that language revitalization isn’t trying to oppose all language change. What some people call “language degeneration” or criticize about how the younger generation speaks is actually a reflection of their ideology on language change. In truth, languages are living and changing in kind with their speakers. Sounds change, new words are created or borrowed from others, and other words die, but it’s all the same language.

The idea of languages degrading with time is divorced from this reality. The goal of language revitalization is not to freeze it in time, it’s to keep it alive. Even then, it’s impossible to stop linguistic changes. Try as anyone might, from people who are picky about grammar to governments trying to control languages, they will continue to evolve and change.

Even during revitalization, a language is changing. Maybe a vowel or consonant shift occurs, or a sound is phased out entirely. Maybe new loanwords are borrowed into the language. In many cases, the languages around the one being revitalized also change and borrow words from it! Revitalization isn’t to stop change, it’s to stop the loss of a language. While some changes, like excessive borrowing, are a sign of ongoing language shift and thus are trying to be prevented, these are the most extreme examples that create a Theseus Ship effect – how much of a language can you borrow before it replaces it? In most cases, those loanwords will still live on.

A Note on Translation

Before talking about why Māori Pleiades is significant linguistically, I want to clear the air of a common misconception on what the translation is in the sense of how it interfaces with traditional Māori culture. Finding perfect information on this is difficult.

Flesh and Blood is a growing game with an enthusiastic playerbase, but it has some catching up to do with the giants of the TCG world.

Māori only has 240,000 speakers, and only 50,000 claim to be native speakers.

The overlap of these two groups had the potential to be – and in all likelihood, is – incredibly small.

LSS, therefore, had a very difficult task. They needed a group of translators who play FAB enough to understand how rules text needs to be written and represented, but those translators also needed to be among those 50,000 native speakers. There’s some room to adjust on either of these metrics of course, but the ideal candidates are an incredibly small batch of people.

It’s also important to note that Māori is not in the same language family as English, or any language FAB is printed in for that matter. When translating between two languages, and especially from distinct language families, a word-for-word translation isn’t going to make much sense. A good translator needs to interpret the text into language and cultural norms.

There’s an additional layer of complexity on top of this, however; no FAB card has ever been printed in Māori before. This means Māori Pleiades will serve as a template for future Māori cards, if there ever are any (and for reasons I’ll get into, I really hope there are). To make matters even more difficult, errors in this space tend to stick. For example, Magic: the Gathering incorrectly translated “goblin” into Spanish 25 years ago, and they’ve been forced to continue to use it even today. All of these factors put a great deal of pressure on the multiple translators LSS claims they used.

What translation I’ve cobbled together is mostly from Māori speaker’s social media posts about the card and its translation, and some technical linguistic know-how in navigating a dictionary of a foreign language. It’s possible in doing so I’ve gotten something incorrect, so don’t hesitate to let me know if I did.

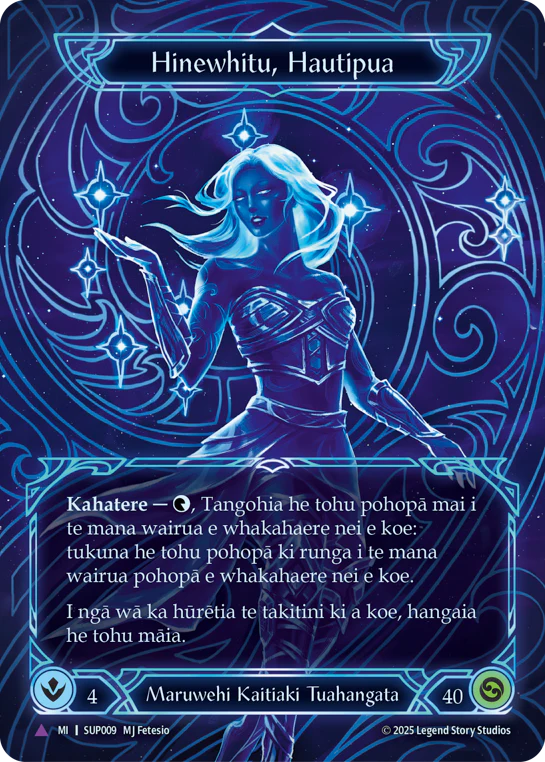

The Māori translators for LSS opted to translate Pleiades, Superstar as Hinewhitu, Hautipua. As best I can put together, the decision for the “Hinewhitu” part is evoking the constellation Pleiades without referencing a specific mythological figure. “Hine” is both the singular and plural affix form of “woman,” although in the most literal sense it refers to “daughter” or “girl.” “Whitu” means “seven,” and isn’t constructed on the card to be “seventh.” Literally, her name is “Seven Women.” Contextually, however, some Māori translate it as “Seven Sisters,” because that is the name given to the Pleiades star cluster. It could also be “Seven Daughters” as a closer rendition to connotations the cluster took on in other parts of the world.

The traditional Māori name for the cluster is Matariki. Matariki is the “mother star” of the cluster, with her six daughters, which would likely give a different translation – or the literal use of Matariki as the name, which carries significance in traditional Māori belief today and is a public holiday in New Zealand. In other words, it’s extremely likely they didn’t use a Māori name for the card (which might seem obvious since it’s not named Matariki, but it would be foolish to think that’s the only name because a cursory search didn’t find others), but rather translated the literal meaning of Pleiades into it.

“Hautipua,” when used as a noun, almost exclusively refers to star performers and idols. It looks like it’s a direct translation of “Superstar” into the lexicon.

Putting it all together, it seems unlikely that this translation is framing Pleiades as a specific mythological figure, as I’ve seen claimed before. This is the conclusion the few Māori speakers I’ve seen comment on this came to as well. This makes a lot of sense given the likely closest choice, Matariki, is both the name of the cluster and the national holiday observing its significance to the Māori. Furthermore, “Seven Women” would be a little odd as a literal mythological figure, as some Māori observe it as nine stars, like the Ancient Greeks and other cultures did. The name is wholly made up, and is very much the scientific categorization of it being seven stars translated into Māori; if it was rooted in cultural significance, it might have been Nine Women instead. It’s possible that was considered by LSS, but that’s just guesswork.

Why Hinewhitu Matters

I’ve done a lot of explaining the science and practical side of linguistics and language revitalization, but this is inherently an article about a FAB card. So what gives? What actually makes this card so important?

To my knowledge, LSS has accomplished multiple firsts here. It is the first time a trading card game has printed anything in a Polynesian language, and the first time printing a card in a minority language. (I’m using this in a sense of totality; for example, different dialects of Spanish are minority languages in parts of Asia, and plenty of Spanish cards exist – but those communities are likely not the target of Spanish printings.) While the first is a cool achievement in itself, the second one is what I want to focus on.

Māori revitalization kicked off in the 1970s with the Māori renaissance, and has largely been successful. Today, completely immersive schools exist for the language, and many business and government offices use Māori titles alongside English ones. Some even only have a Māori name now. Māori is front and center on some television and radio stations as well. While some of these changes are ongoing since the start of the renaissance, sweeping and noteworthy efforts started within the last decade. Books, mostly international works including recognizable titles, are being translated into Māori. Disney movies are being dubbed into the language now. Major international companies like Google and Microsoft began offering classes in Māori. All of these are making the language more known in its own region, where it’s existed for as long as the Māori have existed.

However, these don’t bring the language to the wider world’s attention. It’s not a secret that international attention is a powerful tool for recognition. Refer back to when I said languages like English and Mandarin are becoming preferable in some regions due to social prestige transferring from economic power. International attention isn’t mono–directional towards language replacement, however.

When I was studying Irish in my undergrad years, many of the sources I was directed to regarding Irish revitalization were social media accounts spreading language facts, information, and ongoing policy updates. These weren’t just trying to serve the Irish populace: many of them had a clear aim at people outside Irish-speaking communities and to educate them on the language and its importance. Because social media algorithms try to promote what’s being seen already, these accounts tried to circulate as much information as possible to anyone who would see it – and because social media is international, they often had international audiences once they gained traction. It would be very hard to figure out how much international engagement impacted Irish on its rise to social prestige in Ireland again, but it most assuredly played a role.

Irish isn’t the only example, either. Scots poet Len Pennie reached social media stardom educating the masses about her language, one word of the day at a time. Suffice to say, knowledge of Irish and Scots, and the social issues they are central to, are more well-known around the world thanks to social media.

LSS is contributing the same phenomenon here for Māori. By printing a marvel in Māori, LSS is circulating a minority language on a prestige item in the hobby; and because it’s so sought-after, it draws a lot of attention to the language as well. That may pique some players’ interest, and get more people reading about Māori when they otherwise wouldn’t have. If you’re reading this article because you saw Māori Pleiades, that means it worked. Just like with Irish and Scots, the wider attention is a net-good for the Māori and their language’s future.

If you’re reading this article because you saw Māori Pleiades, that means it worked.

This is a gift that keeps on giving. As long as Pleiades is in the eyes of the playerbase, Māori Pleiades will attract more attention to the language. As the game grows, so will the number of people paying attention to Māori’s current state. With any luck, this has a similar impact that social media has on minority language awareness, and translates to real support. Who knows, maybe there’s future Māori printings in the pipeline to shed even more light on this language and people, fighting for their acceptance and place in society after a long history of oppression.

Conclusion

We don’t know how far along New Zealand is on its goal to have one million people speaking Māori by 2040. There hasn’t been a published survey that I can find since these efforts started going noticeably further a decade ago. Even then, a decade isn’t very long for developing new speakers. It’ll likely take a generation or two before Māori is as widely spoken as they hope it will be - but thanks to LSS, they’re one small step closer than they were before.

My sincere hope is LSS continues to spotlight minority languages in the marvel slot. It’s a wonderful way to not only educate players about the wider world, but to also celebrate the different communities that make the world, and this game, so awesome to be a part of. I hope not just Māori, but Irish, Basque, Mayan, and others come to be a part of Flesh and Blood and represented in the community built around shared in-person play and the tangible world around us. After all, they’re a part of the world Flesh and Blood believes is bettered by a community of gaming. I know I would be happy to have them along for the ride.